January 2021: Addressing Climate Change in School and Community: Learning, Discussing, Doing

Theme's playlist

Expert Panel

Addressing Climate Change in School and Community: Learning, Discussing, Doing

Recorded: Jan 13, 2021 3:00 PM ET

Description: This expert panel will lead a conversation about three strategies for engaging learning and teaching about climate change, as exemplified in selected Multiplex videos: [1] as part of the curriculum, [2] as a focus of citizen science, and [3] as part of the debate in communities at large about the reliability and meaning of emerging science.

Discussion

Share your thoughts on the videos of this playlist.Related Resources

TERC is designing and field-testing activities in collaboration with the Manomet Center of Conservation Sciences as part of the Climate Lab project funded by the National Science Foundation.

Evidence of learning science concepts and practices, student persistence, and the enthusiasm of participants, teachers and coaches, convince us that the Challenge structure and format is highly worthy of further development and investigation.

Combining the creative process of film production and its engaging storytelling and artistic components with science learning allows students to take ownership over their learning process and makes science accessible to learners who might not be reached through traditional science classrooms.

Curricula and learning resources for educators to engage students in authentic and current science about climate and ecosystem change.

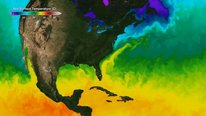

This Network--its tools, people, and guides--is designed to be a resource for scientists and communities alike who are working to design projects to engage all kinds of people -- from middle school students to seasoned sportsmen -- in collecting and considering data to reveal new patterns and new understanding of how climate change is impacting our region’s species, communities, and habitats.

The goal of the Building Systems from Scratch project was to create a truly integrated learning experience that focused equally on climate science, computational thinking, and game design. On this site, materials and curriculum, games, and links to the project’s published research can be accessed.

This challenge is open to 8th – 12th grade STEM teachers who want to engage their students in problem-based learning, doing STEM projects with the potential for real-world impact in mitigating climate change. The I2M Challenges, structured to align with NGSS practices, can work in different school contexts.

GECCo is an energy conservation program for Junior and Cadette Girl Scouts. When girls participate in GECCo activities, they earn patches as they explore how they use and waste energy, how their energy use directly connects them to climate change, and how to change their energy-use behaviors.

Climate Lab is a program through which students learn about and collect data on biological indicators of climate change. Our goal is not only for us to give participating middle-school students and teachers an opportunity to learn from and work with real scientists, but to also compile student data that contribute to a nation-wide citizen science database. Opportunities and resources for teachers and students.

The networks of relationship and conversation within a community can be thought of as an invisible fabric—one that holds, shapes, and expresses the content, value, and consequences of science, the meaning of science for its members.

Brian Drayton

Climate change education is far too rich a topic to fit into one hour! Our panel discussion will leave many avenues unexplored — this discussion aree will be active for the next 3 weeks, and I hope you'll make use of it to pursue your interest further with your colleagues in the field.

I want to direct your attention to the videos in the playlist. I chose them because they exemplify many different strategies for grappling with climate change as a scientific and a policy or public-health concern. What do you think about their choice of audience(s)? About the pedagogical strategies used? About the complementary strengths of formal, informal, and community-centered work? How does your work compare or contrast? Do you see something you'd like to try in your own work?

And most important — do you see ways to incorporate some or all of these approaches in your work going forward — whether research, materials design, education, or community action?

Gillian Puttick

Brian - Thank you for your invitation to join the panel for this month's Theme. I look forward to the discussion, especially exploring ways that we can all leverage the work we do to reach more people on this critical topic and move our communities to take action!

Brian Drayton

During the chat, KarenJane N wrote: "Can you share link to your where’s Waldo? - might be in above links?? "

This activity was developed for the Climate Lab project, a collaboration betwen Manomet and TERC. The lesson materials are housed on the Manomet site, and can be downloaded from there. The "Waldo" activity, which was the first installment of the "signal vs. noise" thread, is in Lesson 1 (though there are follow ups in the other lessons as well) . Here's the link:

https://www.manomet.org/project/climate-lab/

Alan Peterfreund

Does the focus on values (which many of us hold deeply) help or hinder us in getting the engagement in the science? Many people (including many of our educators and researchers) have a strong belief system that drives us to be involved in the climate change discussion and educational outreach. Given the politicization of our public discourse, I wonder whether we are clear about how we present and focus on the science of climate change in a manner that allows the politics and call for action being a response to a deeper scientific understanding.

Brian Drayton

Hi, Alan,

This is an interesting question. The needed kind of "deeper scientific understanding", in my opinion, varies a lot with who the learners are. As you know, more knowledge as usually tested does not translate into more concern about the climate, and more knowledge, in a propositional sense, does not translate into pro-environmental action. There are so many modulating factors!

For younger kids, it seems to me that the main thing is to build their attentive and respectful acquaintance with the natural world as they encounter it. How does it work? What happens around the course of the year? How do things vary, year by year? Information about climate change needs some context, and at the early years, my prejudice is for doing it on an "as needed" basis,

Older kids need the same thing, but in addition can handle information about distant ecosystems Starting in middle school, kids are beginning to engage with public welfare sort of ideas, and so drawing on their growing awareness of some aspect of the climate change work can be related naturally to some action they can take. Recycling and composting at one end of the spectrum; citizen science or policy advocacy at the other. (not quite sure what spectrum that is, but you get my drift).

An awful lot of adults don't know much about the natural history of their own area, much less "globally," so there is much to be said for citizen=science and similar activiities.

People have to understand to some extent what is at stake, and how climate change is affecting things they care about.

So most of my education work is aimed at that focus of knowledge, and I try to make sure that my intense desire for active response is only visible to the learner in fairly contextualized ways. It's ok to say, "The world is changing in the following ways," but you have to help people understand what it is that is changing.

That's my 2¢ on this. Working with teachers or other adults one can be much more direct, and engage in argumentation based on various kinds of data — but the widespread ecological ignorance in this country needs to be kept firmly in mind.

Billy Spitzer

I agree with Brian on the point that in working with adults "People have to understand to some extent what is at stake, and how climate change is affecting things they care about." We all view issues such as climate change through the lens of what we already care deeply about. There is a great deal of research that shows that in order to effectively communicate about climate change in a way that supports effective, collective action we need to frame the issue in a way that connects to widely held values, explains the basic mechanism of how it works so that people can link the problem to the solutions, and provides examples of realistic solutions that match the scale of the problem. Our work on the NNOCCI project (see "Constructive Dialog about Climate Change" video in the playlist) shows how this plays out in an aquarium/zoo/nature center setting.

I think deeper scientific understanding is good for its own sake, and for the sake of developing the next generation of scientists. But it's not going to lead to concerted public action in the time frame we need. On the other hand, climate change is a multigenerational challenge and we need to build the capacity that we are going to need to address it in the future.

Brian Drayton

Thomas F. wrote, in the chat, "Working on modeling climate change with students in Michigan, I’ve noticed that students are more motivated to act than they are scared of their future. They also note....that they need to consider human behavior in the context of their (Earth) science class… not just science."

What age are these students? What do you think has tipped them towards action rather than anxiety? It sounds like a "Greta Thunberg" effect, but I imagine there's more going on!

Thomas Farmer

Thanks for pulling this observation out of the chat Brian. My comment mirrors an observation by the teacher I'm co-developing elements of an Earth Science/climate change curriculum with who stated "students are more motivated to act than they are scared of their future." These students are high-school age, typically 10-12th graders, and of mixed ability levels, racial, and economic backgrounds. While the teacher's comment bears out in my classroom observations of this N=1 class, I'm not sure how generalizable this comment is (!)

I speculate from student statements such as "climate change is already happening" and their acceptance that modern climate change is driven by human-derived excess greenhouse gases that the grand challenge of climate change has been part of these students' reality "forever." The question to them now is, "Can I do anything about it?" I'm not sure that they're as motivated to act as many of us in this forum (or Greta Thunberg!) I think we have our work cut out for us here.

Regarding inclusion of human behavior, the research questions of the STEM+C grant I'm working on focus on use of modeling to deepen content understanding across high school science disciplines, computational thinking, and systems thinking across high school disciplines, not specifically climate change. That said, it's become clear that "science only" climate models are incomplete from a systems thinking perspective where students define a problem space (increasing temperatures, crazy weather, human/eco system mayhem) then try to identify "levers" to reduce or reverse negative effects. This has come up both in class and in other climate-related groups I've been part of such as the "Climate Change Education Collaborative" based in Vermont.

Billy Spitzer

I think there is often an unexamined assumption in climate and environmental education that understanding, awareness, concern and emotions lead to action. Here is a good article that questions that approach:

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748...

Brian Drayton

Thanks for this exchange, Tom & Billy. I think another piece of the motivational puzzle is that people respond to the challenge, and the feeling that "something must be done by someone" when they are offered plausible opportunities for action within their reach. This has been shown to counter deer-in-the-headlights apathy or even despair.

Billy Spitzer

I really enjoyed the panel discussion and thought I would add another perspective regarding community-level education and engagement. Complex issues such as climate change necessitate changes in our collective behavior and public policies. Efforts to advance science or environmental literacy have fallen short, in part because they focus on individuals rather than on social change.

In 2018, the National Academies published a report How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures, which introduced the concept of science literacy at a “community” level in addition to an individual level. They argued that “science literacy in a community does not require each individual to attain a particular threshold of knowledge, skills, and abilities; rather, it is a matter of a community having sufficient shared resources that are distributed and organized in such a way that the varying abilities of community members work in concert to contribute to the community’s overall well-being.”

A community-based approach is more likely to be successful since it can focus on concerns of value to the community; utilize scientific knowledge as a means to public ends; and involve deliberation, collaboration, and other forms of civic participation to work toward community-level solutions that are socially acceptable, feasible and effective. This approach can create the conditions under which communities can participate in joint meaning-making, consistent with a “non-persuasive” approach that promotes understanding of causes and consequences rather than experts advocating particular policies or actions.

Brian Drayton

I have often thought that the core goal for climate change education is to affect the "common sense" of the community-- to get the community to the point that people get used to hearing folks they respect take it for granted that climate change is a problem (quite aside from agreement on specific policy responses) -- then we can talk about ways and means, timing and resources, rather than an existence proof. There is usually variation in a commnuity about almost every point of science. For example, I think there is likely to be a proportion of almost every community that prefers homeopathic remedies rather than "allopathic." But the homeopaths rarely try to interfere with funding for public health clinics, for example...

Billy Spitzer

To further refine the discussion of "community" here, there is a line of argument from the sociologists Gary Fine and Brooke Harrington based on the concept of “tiny publics.” They define tiny publics as “small groups that are a basis for affiliation, sources of social and cultural capital and a support point in which individuals in the group can have an impact on other groups or shape broader social discourse.” The cognitive scientists Wolff-Michael Roth and Stuart Lee argue that these kinds of group affiliations where scientific literacies are negotiated and grown. So, a "community" (as in a geographic community) may very well not be monolithic in its values, beliefs and understanding.

Brian Drayton

yes, I think this is right. I have been working on a parallel line of thinking, which is examining how in-group expertise ("vernacular science") incorporates identity values into their interpretation of interest-relevant science content. I think this is a significant contributor fo the complex that we call "public understanding of science," and it's often quite parallell to, distinct from, whatever mainstream science the group participants may hear or know.

I think this requires a different research approach than is usually taken to such studies. Up close and personal (ethnographic).

Betsy Stefany

Thanks for framing and defining the varied approach to these communities. The "up close and personal" requires a strong commitment of time to ensure trust and activities that involve multiple opportunities to develop analysis from points of view that can be translated to terms that relate and become the language of that community.

Thomas Farmer

An interesting example of high school students' response to a full-year climate change course developed by their teacher, Tim Muhich, at the Battle Creek Area Math and Science Center. Symposium with big names and second day for teacher PD using existing "general" curriculum.

Brian Drayton

Iin the chat, Colin D. wrote:"one provocation: Behavior change models are based on the idea that we know the end point - we know precisely what needs to be done. Do we need a more humble, and open-ended, approach? Given that mitigating climate change is social, not just scientific, problem?"

This makes sense to me, but on the other hand, doesn't this rest on a diagnosis of the gravity of the sitation we are facing — and the pace at which it is unfolding? I would love to see a model of behavior change that actually includes elapsed time as one of the variables!

Billy Spitzer

I would argue that we need an aggressive, collective and innovative approach... this is an issue that demands rapid systems and social change. "Behavior change" implies that this is an issue primarily of individual responsibility.

Gillian Puttick

I wonder whether people who begin to take individual responsibility are not perhaps more motivated to be galvanized into action when, for example, a Greta Thunberg comes along? Starting with individual responsibility can lead one into community action with like-minded people. I think its possible to draw on both bottom-up individual action and top-down approaches...

Brian Drayton

yes, I think that 350.org is an example that works both up and down, so to speak.

Brian Drayton

In the chat, Willow D wrote "Willow D: Keep any suggestions coming on early education related to this! Reggio Emilia is very compatible with scientific inquiry rooted in community" and Ysaaca wrote, "Ysaaca A: As a teacher educator (in early childhood & elementary ed) I would love to know more resources for how we can better prepare future teachers to teach about climate change & climate justice"

What promising resources can you all suggest?

Brian Drayton

"The Greta Thunberg effect" - A propos of motivation to action, there is a new paper out about the impact one person can have in motivating others. The abstract says:

"Using cross-sectional data from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults (N = 1,303), we investigate the “Greta Thunberg Effect,” or whether exposure to Greta Thunberg predicts collec- tive efficacy and intentions to engage in collective action. We find that those who are more familiar with Greta Thunberg have higher intentions of taking collective actions to reduce global warming and that stronger collective efficacy beliefs mediate this relationship." The article can be found at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.111... (no paywall!)Gillian Puttick

Yes! I just responded to Billy's post about "behavior change" representing just an individual responsibility, while aggressive collective action is what is needed. Perhaps models of behavior change are relevant both at the individual and at the collective level.

Billy Spitzer

Just to be clear, I am not saying that individuals bear no responsibility. But community-level action and larger systems-level changes are absolutely critical to making real progress here on a scale and pace that matters. And, community-level action needs to include civic action not just consumer action -- including advocacy for changing the systems and policies that matter including energy, transportation, buildings, etc. (see Project Drawdown for a good analysis).

Climate change has been "sold" for far too long as an issue of consumer choice. This has been an intentional strategy pursued by fossil fuel companies to deflect their own responsibility (see Merchants of Doubt by Conway and Oreskes, for example).

Brian Drayton

Amen.

At present, it seems to me that individual or local action can [a] provide a way of turning interest or anxiety into some outward response; [b] make some changes; [c] motivate others to take that steps at their own scale; and [d] provide an opportunity to see how all such efforts are negated without massive political and economic re-orientations — creating productive frustration, so to speak!

Betsy Stefany

I have to agree that it takes an individual to feel secure to engage with youth who are frustrated by the generation that speaks strongly with data but fails to show working models of progress that they can pick up on and carry forward. These individuals are hard pressed to find "steps at their own scale" but also that will be impactful to turn heads. The capture of major signs of changes also have lost their power to engage and transition the energy into positive results. The drama in fact is by definition from the amazement of the news.

The phenomenon of changes are occasionally small and going unobserved as well as the large events, so should the efforts to engage be less structured? Could what simply avoids events over time be a factor to define sustainability?