- Ryota Matsuura

- Assistant Professor of Mathematics

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- St. Olaf College

- Al Cuoco

- Distinguished Scholar

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Education Development Center

- Glenn Stevens

- http://math.bu.edu/people/ghs/index.html

- Professor of Mathematics

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Boston University

- Sarah Sword

- Senior Research Scientist

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Education Development Center

Assessing Secondary Teachers' Algebraic Habits of Mind

NSF Awards: 1222496, 1222426, 1222340

2016 (see original presentation & discussion)

Grades 9-12

In this video, we will describe a paper and pencil assessment intended to measure secondary teachers’ algebraic habits of mind.

Mathematics, Research / Evaluation

Boston University, EDC, St Olaf College

Related Content for Assessing Secondary Teachers' Algebraic Habits of Mind

-

2017Assessing Secondary Teachers' Algebraic Habits of Mind

2017Assessing Secondary Teachers' Algebraic Habits of Mind

Sarah Sword

-

2015Mathematical Habits of Mind

2015Mathematical Habits of Mind

Al Cuoco

-

2019Studying Teachers' Mathematical Habits of Mind

2019Studying Teachers' Mathematical Habits of Mind

Sarah Sword

-

2015Exploring the Infinite Possibilities of Dynamic Geometry

2015Exploring the Infinite Possibilities of Dynamic Geometry

Brittany Webre

-

2016Transition to Algebra

2016Transition to Algebra

June Mark

-

2020Engaging Multilingual Secondary Math Learners in Discussions

2020Engaging Multilingual Secondary Math Learners in Discussions

William Zahner

-

2021Theory-based Computational Analysis of Classroom Video Data

2021Theory-based Computational Analysis of Classroom Video Data

Christina Krist

-

2017Preparing Student for Success in Algebra

2017Preparing Student for Success in Algebra

Maria Blanton

This video has had approximately 334 visits by 300 visitors from 89 unique locations. It has been played 137 times as of 05/2023.

Map reflects activity with this presentation from the NSF 2016 STEM For All Video Showcase website, as well as the STEM For All Multiplex website.

Based on periodically updated Google Analytics data. This is intended to show usage trends but may not capture all activity from every visitor.

show more

Discussion from the NSF 2016 STEM For All Video Showcase (16 posts)

Gerald Kulm

Senior Professor

Hi. How did you choose the components of mathematical habits of mind? Did you do a factor analysis or other approach to determine the relative contribution of each component to the total? Please provide a little more information about the rubric.

Ryota Matsuura

Assistant Professor of Mathematics

We recognize that we could have measured many, many habits of mind. Focusing on three habits has allowed us to create an assessment that is not too burdensome to use. We started with a list of 40 mathematical habits of mind, gathered from the field (including the CCSS SMP), from advisors, and from our own experience of mathematics, and first thought about which of those habits we could measure using a paper and pencil assessment. We then used a process suggested by our methodologist to determine which of those were most “central” habits.

We then parsed the habits for measurement purposes – for example, the two processes of seeking structure and using structure in SMP7 look different when people actually do them, so we are studying them separately. We also chose the habits that we felt we could capture in paper and pencil format. (Fee free to contact us for more details on the methodological process used come up with our current list of habits.) After multiple rounds of field testing of the assessment, we did carry out some analysis to investigate the relative contribution of each of the three habits we were measuring.

The rubric was built from teacher data – our assessment advisors predicted that the data from completed teacher assessments would “clump” around particular responses, and indeed, that happened. We then used those clumps as the basis for exemplars for a scoring rubric, and invited a collection of nationally esteemed mathematicians (all of whom are deeply immersed in education) to choose the scores for each exemplar/clump.

For information about the assessment and the rubric, please see: Sword, S., Matsuura, R., Gates, M., Kang, J., Cuoco, A., & Stevens, G. (2015). Secondary Teachers’ Mathematical Habits of Mind: A Paper and Pencil Assessment. In C. Suurtamm (Ed.), Annual Perspectives in Mathematics Education: Assessment to Enhance Learning and Teaching (pp. 109–118). Reston, VA: NCTM.

Al Cuoco

Distinguished Scholar

Sarah and Ryota detail their development process quite well. Working through the list of 40 mathematical habits made for many fascinating meetings as the project staff talked through the different perspectives emerging from our own experiences and those of our advisors.

A couple comments about the ones that made the final ``cut’’:

Mary Fries

Thanks for this video! It’s always interesting to hear about the habits of mind research you’ve been doing with PROMYS teachers. Is there a place we can see more PROMYS problems?

Sarah Sword

Senior Research Scientist

Hi Mary – if you’re asking about assessment items, just shoot me an email and I can send them. If you’re asking about actual PROMYS-like problems, there are lots of places to find that kind of content. One example is the recent AMS collection of PCMI-SSTP books: http://bookstore.ams.org/SSTP. We also have content from a number of EDC seminars that have been developed over the years but are not yet in published form – we can get those to you if you’re interested. Thanks for the question!

Brian Drayton

Do you discuss the assessments with the teachers who’ve taken it? I could imagine that it really helps them think about student thinking in new ways, as well as helping them feel more interested in watching themselves think about the math they’re teaching. Could turn into a habit, so to speak.

Sarah Sword

Senior Research Scientist

Hi Brian, thanks for asking. We often do discuss the assessments with the teachers who have taken it. In the early days of development, those conversations had a pretty big impact on the development process. Now that it’s being used as a pre-post assessment, we don’t usually talk about it after the pre, but if project time allows, we do discuss the items and the assessment as a whole after the post. As you predicted, those conversations are pretty interesting. It’s a concrete way into starting a conversation about the Standards for Mathematical Practice, for example.

Al Cuoco

Distinguished Scholar

And teachers have been involved in other ways. For example, teachers at Lawrence High piloted some of the early drafts, and some teachers in PROMYS spent some afternoons coding responses from a pre-test.

Michelle Perry

Researcher

I can see the value of the paper and pencil assessment. Do you think you would be able to get the information you are looking for from a computer-based assessment?

Ryota Matsuura

Assistant Professor of Mathematics

It would depend on how much of teachers’ thinking we can capture in a computer-based assessment. As described in the video, we’re interested in how teachers approach each item, not necessarily the solutions that they obtain. Early in the project, we tried using multiple-choice items, but this wasn’t helpful in capturing their thinking/approach.

So, coding does take some time—-but our rubrics have been refined to the point where most teacher solutions tend to fall into one of the codes, and we can identify this pretty quickly.

M. Alejandra Sorto

Hi Sarah and Ryota! So excited to see the project developed with such as success. I would like to try your measures with my population of teachers (see videohall/p/700 for more detail :)). One of the factors we included to explain variation on ELL student learning gains was Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) construct, but we did not see any significant effect. We are wondering if your measures would be more appropriate – our teachers are middle school and most of them teach algebra. What do you think?

Sarah Sword

Senior Research Scientist

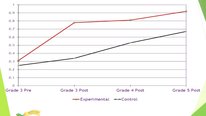

Hi Ale –

Thanks for writing. It might be worth trying the measures out with your next cohort. The assessment works better with teachers who have experience teaching algebra (or are comfortable with it) because of the content – although it’s not a content test, the items are rooted in algebra content. One of the things that may be useful is that it’s possible disaggregate the scores by language, structure, and experimentation – so in one of the pre-post field tests, teachers’ scores improved overall, but their “structure” scores improved the most. That was handy, because the course focused on algebraic structure. (We weren’t the instructors, by the way.) So even if the whole assessment isn’t a fit, some component may be. Shoot me an email if you’d like to take a look at the assessment. ssword@edc.org. Thanks again!

M. Alejandra Sorto

Thanks Sarah for the explanation and the alternatives to the measures. I will contact you to obtain the assessment. Besos!

Sybilla Beckmann

I like your example of looking for structure in a quadratic in order to reason about its maximum value. But to what extent do you wind up measuring a habit versus actual mathematical knowledge about a particular way of reasoning that is possible in certain kinds of situations?

Al Cuoco

Distinguished Scholar

Hi Sybilla,

That’s always a worry—-essentially distinguishing special-purpose methods (``this is how I factor quadratics’’) from general-purpose habits (I look for ``hidden meaning’’ in algebraic expressions). Both trigger automatic responses, so they are not easy to disentangle. We tried to create a larger collection of items that would allow a teacher who’s used to transforming expressions (mentally and on paper or in CAS) to invoke that habit in seemingly different situations. For example, another item asks something like ``Suppose a+b = 9 and ab = 16. Find the value of a^2+b^2.’’ Teachers who invoked structure expressed a^2+b^2 in terms of a+b and ab. Others found a and b (a messy calculation), squared them, and added. Items like this are enough off the beaten path to give us some confidence that we are measuring general ways of thinking versus prior instance-specific knowledge.

And how’s things with you?

AlSarah Sword

Senior Research Scientist

Hi Sybilla, thanks for writing. Just to add on to Al’s response – the assessment we built is designed for teachers who have knowledge of algebra content as traditionally conceived, so it’s not content-free. But in most of the items, we are looking at teachers’ choices of approach, rather than if they can respond. That IS a kind of knowledge, and we call that kind of knowledge “habits.”

Further posting is closed as the event has ended.