- Alice Anderson

- Manager of Audience Research and Impact

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Megan Goeke

- Evaluation and Research Associate

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Science Museum of Minnesota

- Adam Maltese

- http://www.adammaltese.com

- Associate Professor

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Indiana University

- Amber Simpson

- Assistant Professor, Mathematics Education

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Binghamton University SUNY

- Euisuk Sung

- Postdoctoral Researcher

- Presenter’s NSFRESOURCECENTERS

- Indiana University

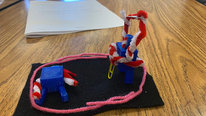

EAGER: MAKER: Studying the Role of Failure in Design and Making

2019 (see original presentation & discussion)

Grades K-6, Grades 6-8

In this NSF-funded exploratory research project we learned from 25 formal and informal educators and over 200 middle-grades youth about their experiences and perceptions of failure while engaged in maker activities. Maker-based learning experiences are often perceived to be prime opportunities for youth to practice the skills of innovation, iterative design and creative problem solving and in the process gain experience with failures, mistakes and setbacks. Through our research in a museum-based maker program, middle school classrooms, and an after-school making and tinkering program, we learned that whether or not youth experience failure and what impact that may have on learning is only one lens on this multifaceted concept.

Our research explores questions such as: What does it mean to fail? When and where is it OK to fail? How do educators support youth through failures? What other words do people use instead of failure? Over the course of the 3-year project, we conducted classroom observations, videos of youth making experiences, interviews and surveys. Our video highlights our key findings on how activity design, educational context, individual differences and pedagogical approaches contribute to learners’ experiences with failure.

Related Content for Learning what failure means in maker experiences.

-

2018Debugging Failure: Youth Resilience in Computer Science

2018Debugging Failure: Youth Resilience in Computer Science

David DeLiema

-

2018Project TACTIC

2018Project TACTIC

Todd Lash

-

2015Enhancing Understanding of Concepts and Practices of Science

2015Enhancing Understanding of Concepts and Practices of Science

Andy Cavagnetto

-

2015Style Engineers: Fashion Through Science

2015Style Engineers: Fashion Through Science

Kristen Morris

-

2016ACES: Algebraic Concepts for Elementary Students

2016ACES: Algebraic Concepts for Elementary Students

Davida Fischman

-

2022Math and Computational Thinking Through 3D Making

2022Math and Computational Thinking Through 3D Making

jennifer Knudsen

-

2019The UTeach Maker Showcase: An open portfolio

2019The UTeach Maker Showcase: An open portfolio

Shelly Rodriguez

-

2017Engineering and Makerspace Experiences for Teachers

2017Engineering and Makerspace Experiences for Teachers

Jennifer Eklund

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Hello! I am Adam Maltese and, along with my collaborators Amber Simpson and Alice Anderson, welcome you to this video about our project on making + failure. Over the last few years we have been exploring how kids engage in making in formal and informal contexts and how they respond when things do not go as they planned. We looked at how youth react to moments of failure and what role adults play in these experiences.

We are excited you're here and hope you enjoy our video. We are very interested to learn about your experiences with failure and whether or not you think it is something we should seek to engage kids in more frequently or something educators should seek to avoid. Please share your thoughts!

Roxanne Hughes

Fantastic project! Did you find differences between informal educators and formal educators in terms of willingness to provide opportunities to work through failure?

Adam Maltese

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Thanks Roxanne! I think it would be hard for us to generalize that finding at this stage, but I'd say that generally speaking classroom educators have been a bit more reluctant given the relation to grades and such. That said, informal educators are often bound by the need to make experience "fun" and failure seems antithetical to that. Do you have a sense or a hypothesis?

Jim Hammerman

This is really important work. Science and engineering and design and problem solving of all kinds requires trying things where you really don't know whether or not it's going to work (as in, do what you expect it to), and then using the information to learn and refine and try again to make closer and closer approximations of what you intend. In that sense, an "experiment" that only tells you what you already know and doesn't give any new information is the real failure. Were people in your study able to reframe "failure" in this or other ways?

Alice Anderson

Manager of Audience Research and Impact

Thanks for your comment, Jim! Two thoughts come to mind.

One aspect we noticed was how training in other disciplines influenced educator's perspectives. Some had an engineering background, so the idea of iteration/process and a design cycle helped them to re-frame failure for learners. The three educators in the video are also artists, and so they always emphasized personalization and creativity with learners as a way to downplay failure as an end-state.

In addition to the influence of the disciplines, we also noticed that failure could re-framed when affordances or limitations of the materials were explored. For example, in one carpentry summer camp, bent nails was a frustrating but totally normal part of the learning process. One instructor made a "Museum of Bent Nails" bucket for kids to put theirs in when it happened. There were many more nails to use - so even though that nail was a failure, it was easy (and even funny?) to keep going onto the next one.

Noah Feinstein

Associate Professor

I love this project, and I really appreciate the way your video opens up some really deep questions in an accessible way. I found myself wondering about different ideas of success that are particular to makerspaces and classrooms, and how definitions of failure might rely on unspoken ideas of success. When you were looking at how people talked and thought about failure, did you also look at how they talked and thought about success in those contexts?

Alice Anderson

Manager of Audience Research and Impact

Thanks, Noah! That's a great question. Our research questions at the beginning of the project were around how youth and educators identified and defined moments of failure during making, and how their definitions aligned (or didn't!). In the interviews, questions about failure ultimately led to conversations about why the learner or educator perceived an event as an failure (what was failing, and and against what standard?). Several of the educators we talked with realized that if they really wanted their learners to reflect on a failure or a struggle ("What just happened there? Why didn't that work out like you expected it to?") they needed to reduce the number of things they wanted to accomplish in a class. That is, they needed to simplify and to slow down so there was time for reflection on those moments that didn't go as they expected.

In addition - and this isn't a small thing - several educators told us they appreciated our conversations around the topic of failure because it had never really been OK to talk about. Through focusing on failure, they discovered their own opinions they didn't know they had. Jan, who you see in the video said to us: "Sometimes you don't know your own philosophy because you don't get listened to for long." It was very important for them to have a supportive space to explore their own thoughts about how failure fit into their teaching philosophy.

Noah Feinstein

Irina Lyublinskaya

I really enjoyed watching your video and applaud your encouragement for educators to have a different look at "failures". Did you have a chance to work with kids of different ages? Did you notice if there is an age difference in the way kids perceive failure? I am also interested whether there is a time limit at how long kids could struggle before they give up and how long educators were prepared to let kids struggle. We find it that elementary school teachers are eager to jump in and help rather than let kids struggle.

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Irina - to add to Alice's response - we have been thinking a lot about how educators play a role in these experiences. In case it's useful, I share our paper (link below) where we took survey responses from many maker educators about their views and how they try to encourage persistence in these experiences. I believe it addresses some of your questions.

Failing to Learn

Alice Anderson

Manager of Audience Research and Impact

Hi Irina. We interviewed and observed kids aged 9-15. There did seem to be a difference in the 9-11 age group and 12-15 age group in terms of how they responded to failure; older kids seemed a little more self-conscious of failing or "not doing it right." Younger learners rolled with it or asked for help a little more readily. However, we suspect that how familiar a learner was with the tools and materials might also have influenced their persistence.

We certainly observed educators and parents jumping in to help. Some educators shared rules they have for themselves - like keeping their hands behind their backs while the talk with learners (so they don't handle their project), asking for permission to touch their projects, or suggesting that learners ask two other people before a teacher. These techniques helped learners retain agency and control over their learning.

Irina Lyublinskaya

Mahtob Aqazade

Thank you for sharing your video! It was so fascinating to read the comments and interesting to learn how coming from different disciplinary knowledge influence the way you might approach/talk about failure. I am curious to learn more about the role of curiosity-motivated explorations in being persistent to continue exploring when facing failure.

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Hi all! We wanted to post another question to the audience about failure - DO YOU THINK IT IS IMPORTANT TO ENGAGE KIDS IN FAILURE EXPERIENCES? WHY?

Rabiah Mayas

Associate Director

Thanks so much for sharing this project with us! Research-based evidence in failure experiences and how they can matter have been long-sought by many of us practitioners in particular. I am curious if your project involved any insights from parents, caregivers and families, as related to how youth learn about, define and experience failure. Does the way failure is (or isn't) acknowledged at home as part of the human experience influence a child's openness and self-perception about their own failure? Did the observations of parents in the makerspaces provide an opportunity to dig into this a bit?

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Rabiah - great to hear from you!

We are quite certain that the treatment of failure at home (and in a youth's past) is quite influential in how they approach failure. We dug into this a bit through the interviews we did with youth when we asked them about their views on and experiences with failure. These were early in the project but I don't remember there being too much mention of parents in the responses but I'd bet that they absolutely have an influence.

One piece of evidence we did have that relates to this is that we had many educators tell us that when there is any type of public performance or demonstration of what the students made, often in the form of a show and tell to parents or caregivers, then this strongly increases the chances that youths would have more extreme emotional reactions to failure in the final stages than if this type of public performance was not part of the expectations. I'd hypothesize that the responses are related to a combination of a student's internal conceptions about failure and what they expect from their caregivers too.

Do you have any thoughts or hypotheses?

Rabiah Mayas

Associate Director

Hi Adam! So happy to see you on here. Thanks for the reply and additional info! In some current work where our team has end-of-program "finale" events where parents and caregivers are present, we haven't looked at emotional reactions to failure vs. during regular programming days. Your note has me thinking that we should.

I've been out of the maker learning space for a brief bit and don't have any current insights, unfortunately. But it always struck me (still does) that failure in STEM-rich spaces can have strong cultural influences, e.g. if STEM is seen as a critical/sole pathway to career and economic stability, families may resist failure as acceptable in any form. Katie mentions this as well below. I know there is scholarship on this kind of family dynamic in minoritized and immigrant populations around classroom learning and athletics, but I'm not yet familiar with work showing the connections to OST learning environments. Adding this to my reading list!

Anne Kern

Associate Professor

Someone once told me a big difference between science and engineering, was scientists want the ideas they put forward to "fail" in order to learn about it, while engineering wants to be sure what they build does "not fail."

How do you think we can ask students to learn from failure and maintain high expectations at the same time?

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Anne - that's a great way to think about the differences. My sense is that the best way to achieve this is to create a culture where iteration toward improvement is a core ideal. This will help to instill the idea that whether failure or not, the idea is that all of our work can improve and that it's important for us to keep working to attain the best possible result. Two ways I tried to do this in my classes is a) making sure students are allowed time for multiple revisions and b) talking explicitly about having them complete versions of an assignment with clear articulation of what they changed from one version to the next. Do you think those options might work?

Katie Stofer

Hi Adam (and everyone), to me, I'm hearing and reading a lot about what the word "failure" means, and it brings to mind criticisms I've heard where for a lot of communities, failure is not an option (or basically, for a lot of privileged populations, failure is a privilege) - aside from engineering as Anne notes. I'm wondering if within the researchers, there might be Failure and failure (like Identity and identity) - attempting and not getting enough points on an end-of-course exam might be Failure (especially if it happens at a time to prevent high school graduation or grade progression, whatever). But little-f failure is more what we're talking about in the culture of iteration. Not sure that would resonate with students, though :)

So yes, I suspect there's a benefit to calling things "drafts" or "versions" instead of failures (which seems more final). I try to tell my research students that what they typically do at the end of a class is usually the first draft of something in the life of a research paper that will be published. I mean even the word "prototype" implies progress. Maybe it's also a matter of redefining the idea of an endpoint or goal as simply a first step, or endpoint-for-now-until-we-know-better. So the expectation as "the best solution given what you know at this point", which I think can still be high. This fits with your model - you could even give them assignments that model this moving endpoint: assignment 1, make X with Y; assignment 2, now make X with Y and Z; assignment 3, remove Y, etc. So it's both about a moving endpoint and a growth in the student - they can both change (and often do).

Are you seeing a lot of reluctance to do the first version/draft, and when you return with comments/suggestions, less reluctance to revise and go from there? I feel like that's what we've set up students to do with the single-end-game test/paper model.

Anne Kern

Associate Professor

I like this thinking, "failure" is such a negative word! No one wants to fail, to be at the bottom. Perhaps we can change the rhetoric here, instead of "fail" what about "improve"? Let's strive to improve, even if something is perfect, perhaps it would be interesting to make it better! Like double stuff Oreos! :)

Adam Maltese

Amber Simpson

Assistant Professor, Mathematics Education

Thank you for your comment Anne. I love your comparison to double stuff Oreos. We are beginning to consider ways to normalize failure as part of the making context. Be sure to continue following our work.

Wendy Martin

Hi Adam and Alice;

Great video! It's valuable to look at how failure can be experienced not as an end but as a learning moment in a larger process--and to understand that in design and making, a failure of a prototype is expected, and a source of data. To answer Adam's question, I have been encouraging program developers that I work with on projects focused on making but also on computational thinking that it is crucial to make the programs flexible enough for kids to mess around, make mistakes, and revise. Not only does that help a learner develop persistence and creativity, it makes the program more fun for the educator or facilitator running it, because it means that the kids can surprise them!

Adam Maltese

Alice Anderson

Manager of Audience Research and Impact

Great comments and conversation! One thing we haven't brought up yet is activity design and materials. In your experience, what sorts of making or tinkering activities or materials are good for practicing persistence through struggles or failures?

Regina Werum

Great video, thanks for sharing. How do you communicate the value of failure (and not just the merit of "grit" and "persistence") to administrators, and to the general public -- especially in an atmosphere where not just students but teachers and schools are erroneously judged by successful student performance on tests that cannot be retaken?

Alice Anderson

Manager of Audience Research and Impact

Hi Regina - That's a great question. Before I offer too many thoughts I think it's important to contextualize our study in the field of making and tinkering education, which already sits on the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Many of the educators and programs we know are less interested in test performance than they are about youth development and 21st Century Skills (e.g. collaboration, confidence, creativity, problem solving, etc.)

That said, I think once we've gotten past what adults think about failure as it relates to learning we tend to see that conversations do come around to values of of 'getting through hard things' which seems relatable for educators, parents and learners. Whether or not people want to use the concept of failure seems less important than the idea that educators do want learners to experience challenge, struggle and risk-taking.

There's a good book called The Gift of Failure written by Jessica Lahey (an educator and parent) that deals with your question more directly.

Sandy Wilborn

Thank you for sharing your video! This is very interesting as we are doing similar work. In our US Dept of Ed i3 project, the Rural Math Innovation Network (RMIN), a group of 30 Pre-Algebra and Algebra I teachers in rural Virginia are collaborating in a virtual network. The are working with peers to create lesson plans that incorporate growth mindset and self-efficacy in mathematics.

Teachers are helping students realize that it is okay to make mistakes and we learn best from those mistakes. They are sharing videos on neuroplasticity and using materials and strategies from YouCubed and Jo Bohler.

Please take a look at our video "If You Give a Teacher a Network" (https://videohall.com/pl/1497) to learn about what we are doing in our project.

Meriem Sadoun

We introduce families who come into the Tinkering Lab space at the Chicago Children's Museum to the engineering design process which encourages iteration and reflection on what worked/what didn't/why/how can it be better. From the start of their time in the Tinkering lab, the families know that failure is part of the process, and iteration or fixing the failures will make their creations better. And that failure is part of being an engineer!

I'm curious, how do you help children work through their frustrations to have a productive response to failure?

Adam Maltese

Amber Simpson

Assistant Professor, Mathematics Education

Hi Meriem. This is a great question and one we should open up to the larger community. How do you help children work through their frustrations to have a productive response to failure? In what ways can we as educators normalize failure within making contexts?

Catherine Haden

Rebecca Lugo

First of all, this is a great video and such an important topic! Well done!

I use the word FAIL as an acronym: First Attempt In Learning; I actually tell my students that I expect them to fail. To support them in working through their frustrations, I have done read-alouds (Rosie Revere, Engineer comes to mind) and pointed out how the characters have dealt with failure. Together we come up with suggested actions they can take when they are feeling frustrated, such a deep breathing, journaling, walking away from a project for a bit, or even looking for ways to help classmates with an entirely different project, which often sends them back to their own work with a fresh perspective. When their projects fail, we look for ways in which they met parts of the criteria and/or constraints and commend them for those things. We give multiple opportunities to go through the design process, noting that it's an iterative, circular process, not a straight line from start to finish.

As an educator, it's so important to embrace failure as part of the process and to encourage our students by focusing on the positive, asking questions to help them discover for themselves what their next steps should be. It is also very important to be honest about our own failures and let students see that we don't do everything right the first time, either.

Adam Maltese

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Rebecca,

Thanks for sharing and for your comment. just the other day I was talking with a few maker educators from museums who were tell me how they help kids work through similar situations. Like your response, nearly all of their focus is on getting them to work through it rather than just "fixing" the problem for them. In talking to them and reading yours it makes me happy as these results add more conformation to the work we published in Thinking Skills & Creativity. Now we just need to work with a wider range of educators to support them in being comfortable with this too!

Torran Anderson

What an important topic! Thanks for sharing your video.

How has working on this project impacted your own view of failure and success in your own work? Has it enabled you to look at the challenges in your project in a new light?

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Torran - personally (and somewhat humorously) my daughter reminds me that I am researching failure and that when something doesn't work for me I need to tell myself to keep working through it! In this project, specifically, I think we have had a few approaches to data collection that didn't work. One was where we were going to collect video from students one day, watch the video overnight and try to ask them about moments of failure two days later. Idea seemed great, but we just couldn't process the data that quickly. So, there have been a few instances like that, but we just keep plugging away and think of alternative approaches to get what we want. So, I think we've generally been modelling good practices in persistence! :)

Amber Simpson

Assistant Professor, Mathematics Education

To continue this discussion, I decided to wear a GoPro camera to capture my interactions with upper elementary students engaging in making activities. It is alarming what you learn in watching yourself on video as I was not necessarily modeling appropriate behavior for the undergraduate students I was working with in the space. I found myself not allowing the elementary students to experience failure as much as I thought (or hoped for). However, being on this project has made me aware of such instances and trying to be mindful of my response (or not) to failures not only in making contexts but other contexts such as an academic setting.

Ellis Bell

Thanks for your video and all the great comments it has generated. The problem persists into the undergraduate years too, are you aware of any work at that level

Adam Maltese

Associate Professor

Ellis - great question! I am not sure if anything comes from the arts or engineering, but I know there is not much from the sciences. We definitely encountered this issue when we were researching undergraduate research experiences and at that time there was little to no work out there about this.

Further posting is closed as the event has ended.